A Jon Post

The more I think about and hope to become more skilled at reflecting Christ to the sick and the dying the clearer it becomes that, despite the simplicity of the gospel, there is no simplicity in the practice it demands.

What is the good news to the 17-year-old boy living in my home whose lymphoma protrudes from his chest, his arm pit, his neck, and his ribs? What is the good news to the 43-year-old widow who lives in the liminal space between living and dying, unable to know if her cancer is growing as she does radiation therapy or receding? There are 14 men and women living in my home. Nearly all of them are unsure if they inhabit the land of the living or the land of the dying.

Please imagine that with me.

They sincerely do not know if the cancer detected in their bodies is responding to the poison dripped into their veins. The do not know if the speed-of-light radioactive particles ripping cell membranes and dignity to shreds is doing the same to their cancer, giving way to more living or simply prolonging an already prolonged dying.

So we wait in the unrestful place of helplessness.

Social workers and developmental experts like to talk and write about something they call “learned helplessness”. This is the idea that, after prolonged experiences of shock, pain, and betrayal, people and animals learn that “nothing they do matters”; there is no act, real or imagined, that could provide an escape from that shock, pain, or betrayal. Surprisingly enough, only within the past few years have researchers discovered that the original theory of “learned helplessness” was precisely backwards; that is, passivity in response to shock is the default, and that we learn that we can escape from that shock or pain. We learn control, we learn that we have power, we learn that escape may depend on our own responses and actions (if you are interested in this, there is a very neat article here about it). I’ve realized that it has become important that I unlearn helpfulness in many of the ways I serve at Casa Ahavá.

I mention the above because it seems important to me to enter deeply the spiritual reality (my paragraph about Christ and the gospel), the soul/psychological reality (the above paragraph about learned helplessness), and now I’d like to enter with you into the corporeal reality (our bodies, our dust, our fingerprints).

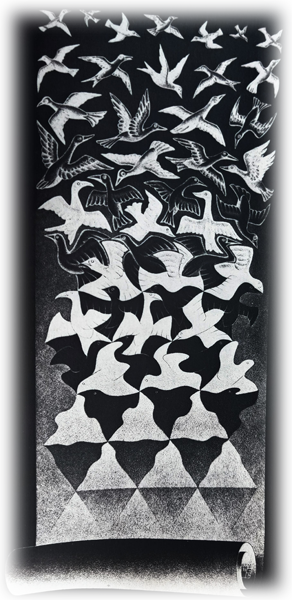

So why helplessness? Well, as I mentioned above, our psyche seems to begin with the assumption that we are helpless. With all of our modern medical advances (at least in North America and in Europe), it turns out our bodies still die. No matter how much we internalize the idea that we are not helpless, no one has yet found a way not to die. We can try and try to learn that we are not helpless, yet there comes a door through which we all pass on our way into our dying.

That door is helplessness. No act, real or imagined, will keep us from the land of the dying.

In Casa Ahavá, in our world of the sick and the dying I ask you to please imagine with me the helplessness of not knowing whether you are living or you are dying. Perhaps you, dear reader, have had cancer or have walked alongside someone who has. Maybe it was Krohn’s disease. Maybe it was HIV/AIDS. Maybe it was Parkinson’s. Maybe it was Alzheimer’s. If you have walked the paths of those dark forests, you may have come across this painful realization: You were taught a lie. You were taught that helplessness is wrong and that there is always an escape. You learned helpfulness. In an age of power and control, someone has tried to convince us that they can be delivered into our own hands.

Is this important to you, dear reader? Is this stuff ok? I truly don’t want to bore you with this but it has felt more and more urgent for me to know the fellowship of Christ’s sufferings (back to the spiritual reality, right?) and this seems like an important pathway through that dark and confusing forest.

So what connects helplessness to the fellowship of Christ’s sufferings? I’d like to quote just a few verses of Scripture here, if you will be so kind as to bear with me:

He was oppressed and afflicted,

yet he did not open his mouth;

he was led like a lamb to the slaughter,

and as a sheep before its shearers is silent,

so he did not open his mouth.

By oppression and judgment he was taken away.

Yet who of his generation protested?

For he was cut off from the land of the living;

for the transgression of my people he was punished

He was assigned a grave with the wicked,

and with the rich in his death,

though he had done no violence,

nor was any deceit in his mouth.

Yet it was the Lord’s will to crush him and cause him to suffer

Isaiah 53:7-10

Does that sound like helplessness to you? It does to me. The man to whom this prophecy refers had all power and authority laid before his feet… and he chose helplessness. He chose to be led away, silent, without protest, crushed, and suffering.

Yesterday I had a long conversation with a 23-year-old boy dying with cancer with a large open wound which has taken away his ability to walk. The cancer has robbed him of his dignity, his privacy, and his strength. And I can give none of that back to him. No action of his or my own, real or imagined, can provide escape from his affliction.

Today I looked a 17-year-old in the eyes as he showed me another painful lump protruding from his flesh and I could not tell if the mass under his skin was greater or smaller than the fear in his face.

For you see, I have no power here. I am helpless.

A wise man recently told me that the whole arc of the Passion narrative bends toward helplessness. Who then am I to seek power and control (helpfulness) when Christ gave those up?

To those of you reading this who pray with us, partner with us, are participants in this broken-to-be-given project that is Casa Ahavá, I say this: The blessing of serving in Mozambique is to become more comfortable with the spiritual reality of helplessness. So: here we are; send us.