A Jon Post

Death came calling.

Who does not know the rasp of reeds?

A twilight whisper in the leaves before

The great araba falls

-Wole Soyinka Death and the King’s Horsemen

Ah, yes… these halls, these steps, this awkwardly steep ramp and stairs. I know them all. I know the patterns made by footfall and old stretcher wheels, each in equal measure, tired, yet determined to bear burdens to destinations.

Ah, yes… this weight on my shoulder, the knees draped over my arm, the smell of necrosis left on my shirt after a head rested there. I know them all and I know the trust and the vulnerability extended in short uneven breaths.

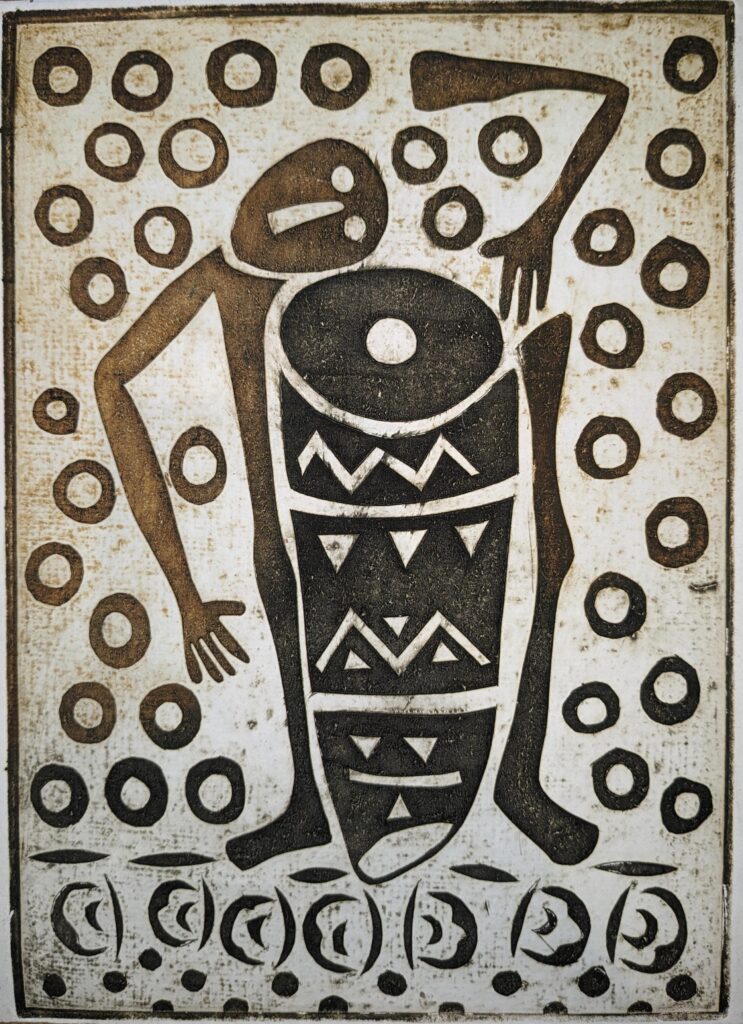

Ah, yes… the drumbeats of the work and the dance rhythms of the desperately ill. I recognize them all and I recognize the weariness shared in them too. We pound the animal skin of the drum together, you and I. We raise and stamp our feet in unison, you and I, and we dance our way into the chemotherapy laden halls of the oncology ward and the constant beep of the heart-rate monitors of the ER. Oh, Aventina and Ussene, we dance our way through this broken land of medicine and mystery hoping for a smile and a few moments rest.

Ah, yes… the wait. The wait. Will antibiotic and transfused hematocrit and a ritual prayer sang over it all bring the miracle? The wait. Will paracetamol infusions and x-rays really do what a chanted “Father, please… not yet” won’t do? The wait.

Ah, yes… the drive home in an empty car. Tomorrow the news will be better. Tomorrow, after a good night’s sleep with a badly placed IV line in your arm and a new dawn, we will dance again. We will dance back down those stairs and back through the hallways back to my car and to my home. It is only tonight that my car is empty, it is only tonight, beloved. Tomorrow we dance again.

Ah, yes… the drumbeats again. The drumbeats of my heart and my breath as I wonder if I should have just stayed. The drumbeats of your heart and breath, too. They slow, beloved. They slow. Mine too. Mine too.

Ah, yes… the next-day-hallways and the dance of the white clad professionals making way for death and the dance, holding up stop signs to interloper and intercessor. Sunlight and disinfectant vie for prominence in the broken tile below our feet where wheelchairs bring their wards. Where are you, beloved? Where do you beat the drum of your heart and your family and your people?

Ah, yes… the wince of the white-coat-wearer, the furtive glance to the side trying to assess how important this question is to me and how much time is needed to answer it. Where is my beloved?

Ah, yes… the dance of the daughter’s tears and the accusation in the wailing… “I worked so hard for her… I worked so hard” she beats the words unto the drum’s animal skin and shell, and she dances to the loss of our beloved. She is dead, she is dead, she is dead, she is dead, she is dead.

Ah yes… the tears of the older brother who holds my hand in his and wonders over and over and over how he deteriorated so fast, how tumor and flesh and grey matter fused to create confusion and sleep and nausea. He is dead, he is dead, he is dead, he is dead, he is dead.

Oh, Ussene and Aventina, oh beloved aunty and uncle, we wail and dance and perform our grief on the dirt-patch of our souls and of our backyard. We walk in the footsteps of the one who offered His own body broken for us, his blood poured out for us. We too, offer our brokenness to you… take and eat. Take and drink of our blood and our grief and dance your way through the stars to the drum beats of your people into the arms of the one who first offered you food from His brokenness.