A Jon Post

I’ve started and re-started this note several times. I knew, I knew I needed to write something and I felt the urge to get pieces of myself and my grief onto this page.

This seems as good a time as any to do it.

While the year is hurtling into March, the end of last year and the beginning of this one have seemed to freeze in place for me. Grief can be cold some times.

Like death.

DIES iræ, dies illa,

solvet saeculum in favilla,

teste David cum Sibylla.

THAT day of wrath, that dreadful day,

shall heaven and earth in ashes lay,

as David and the Sybil say.

Manuel was a hustler, a “get-what-I-can-because-life-won’t-give-me-anything-for-free” kind of attitude infused how he carried himself.

A few years ago, following dreams for a better future, he hopped the border into our neighboring country, South Africa, a nearly mystical land of opportunity and wealth to many Mozambicans born into poverty. All seemed well and he made a habit of sending the strong South African Rand back to his wife and sons to keep them sustained while he bounced from opportunity to opportunity. At the beginning of last year, a small lesion appeared on his shin but he blew it off, knowing that he had no time to slow down in his quest for a better life for his wife and two young sons. After only a few weeks it grew to be too painful to walk so he presented himself to one of the government hospitals in South Africa where they quickly diagnosed him with a bone-deep carcinoma and took his leg above the knee before he could even think through what it meant to have only one.

In pain, and learning to use elbow crutches on his own, he lost his job, his home, and his way of life and limped his way home to a small border town on the Mozambican side of the South African border called Ressano Garcia. There, he tried his luck at facilitating currency exchange at the border for only a month until a lump started growing in his groin above his amputation.

With no way to return across the border he came to the Maputo Central Hospital.

By the time of his arrival the metastatic lump had exploded into a full blown necrotic wound on his inguinal lymph nodes, pouring its cruelty across his leg, his groin, his clothes, and his soul. Manuel had always found a certain comfort in his strength and in the caricature of masculinity he tried to embody. Cancer’s claws often seem to pinch the places it knows will bring the most shame.

When I met Manuel he was a shell of his former self, and I only came to know bits of his story after I invited him to come to my home and began helping him with daily bandage changes. His drive to get home between oncology appointments and his drive to find something or someone that would cure him lent itself to tension between the two of us. But tension doesn’t seem to be able to snap the cable forged from the steel of bodily vulnerability and bodily fluids. Manuel made many mistakes. So did I.

Last week he died in pain while looking for ancestral power from ancestral medicine in the home of his ancestors.

O what shall I, so guilty plead?

and who for me will intercede?

when even Saints shall comfort need?

Selma came back to Maputo and I’m pretty sure she knew what it meant.

She had come here a year prior, done six rounds of chemotherapy, 30 days of radiation-therapy, and gone home to her young daughters with high hopes that her cervical cancer had been eradicated by the toxic combination of oncological regimens.

It was not.

Selma’s cancer did not wait long. Coupling her determination to her weariness, Selma repeated the 1000-mile journey back to Maputo to repeat medical imaging scans and be re-evaluated for a second line of treatment. Her scans confirmed what was already suspected. I remember well sitting in a dingy office with her and a young oncologist, doing our best to hold the space for her grief and to make clear what the limits of chemotherapy were. She smiled, affirmed she wanted to try chemo again, and came to my home.

Months went by and, even as her own body grew frail and thin, she smiled through the pain and drew upon her faith and her family tradition of serving those around her. Selma had a strong will, a ready smile, and nimble fingers. She passed hours of nausea and body-aches knitting special gifts for my daughters, the other patients at Casa Ahava, and even staff members at the hospital. For every other patient at Casa Ahava, her love and her service became a bulwark against the despair brought on by chronic illness.

Six months of chemotherapy could not hold back the malignancy in her bones and her body. She went home to her two young daughters to die. We ache at the missing of her smile.

Last week her right leg stopped working at the hip.

Recall, dear Jesus, for my sake

you did our suffering nature take

then do not now my soul forsake!

Elcina was one of my favorites.

In work like this, much like in parenting, I am sure I’m not supposed to have favorites but my I can’t seem to avoid it sometimes. Elcina found her way into Casa Ahava and into my heart about the middle of last year. Her home is only a two hour bus ride away (still far but much closer than most of the others who come to Casa Ahava) which is usually a reason to disqualify someone from coming to my house. When I initially began telling her oncologist this, he pulled out a mountain of papers, each with a detailed report of her health, each directed to a different service at the Maputo Central Hospital. Cardiology, gynecology, pulmonology, physical therapy, nephrology, neurology, radiation-oncology, my head spun. Elcina’s breast cancer had invaded nearly every system in her body.

Elcina’s mother, who had accompanied her to the hospital, had just returned home to attend to farm and family so she sat alone on her hospital bed when I first came to meet her. As I often do, I asked her what she understood of her disease. As patients often do, she told me the extended story of what brought her to that bed and the many hardships along the way. When she came to a conclusion, I re-emphasized the question, asking what she understood of her sickness today. I have often found it to be remarkable that, given the clearly late-stages of cancer and illness someone is experiencing, they rarely have a cognitive or expressible in words understanding of their illness. Some time ago, this led me to believe in an absence of that understanding in any capacity. After having many of these conversations over these years, however, I’ve come to realize that the cognitive is not the only, and perhaps not even the best, way of understanding and integrating the reality of one’s own dying time. This was true of Elcina.

Elcina came to Casa Ahava and had an amazing bodily bounce-back. Her chemotherapy pushed dark tendrils a little further back, the tube pushed between her ribs into her lungs found plenty of necrotic liquid to pump out and offer air to starving lungs again, her heart medications reduced blockages and lowered blood pressure, and she found her sass again.

I could hear her laugh from 100 meters away.

While weariness did occasionally slow her down, she took to long walks and bus rides around Maputo city, encouraging her roommate to play and laugh a little longer with her in the light breeze of the afternoon. Her two younger sisters came out to visit her and, their little smartphone’s volume pumping its little heart out, they all danced under the shade of our veranda and our mango tree.

Elcina was one of my favorites.

Chemo doesn’t work forever, particularly the handful of old generations of chemo we have here in Mozambique. Liquid secreted through lung tissue and Elcina’s chest heaved a bit heavier when she walked. It pushed through pericardium walls and her heart beat quicker and shallower in its labor to push her chemo-laden blood through her veins.

Her laugh endured. But her energy did not. My urgent visits to the hospital with her increased. Echocardiograms, vacuum tubes squeezed through ribs and lungs, more morphine… and more days spent laying in her bed.

In intimate and emotional conversations Elcina had made it clear that she wanted to die at home with her mother when her time came. “That time” can be reckless in its approach. Elcina’s blood pressure plummeted and we frantically organized for her older sister to come to our home so she could accompany Elcina to her mother. On Elcina’s last day here, a hot day in mid-January, her roommate Isarda, stood faithful witness to what was occurring. Similar to the conversation from 7 months prior, neither Elcina nor Isarda had made cognitive what was happening in the spiritual. Nor had I.

As Elcina slowly edged into the back of our van where we had made a wide space for her to rest as she prepared for her journey home she reached out to her roommate, her playmate, her partner in chronic illness, Isarda..

And yanked her tightly into a sisterly embrace.

“This is not what we agreed to” Isarda screamed through her tears and through Elcina’s silent grasp. “It’s not what we agreed to” Isarda cried out again and again.

Elcina’s hand stroked Isarda’s head through the tears we all let flow. She never said a word.

I took off my shoes.

Two weeks ago, Elcina died in her mother’s arms.

Your gracious face, O Lord, I seek;

deep shame and grief are on my cheek;

in sighs and tears my sorrows speak.

Felicidade was sitting patiently in the treatment room on the floor below the rest of the oncology service.

Her painful IV port protruded from her arm and her drawn face marked the long road she had already traveled to be here, in the oncology ward, hoping for a miracle. She was quiet and hesitant when I first approached her. Her oncologist had recommended I speak with her about coming to Casa Ahava though he didn’t have the time to accompany me in the introduction so she had no idea who I was. Although her family had more resources than most here in Mozambique, they did not have what they needed to house and feed her so far from home so she had spent the previous three months living in the gynecology ward, coming once a month to the oncology ward to get her chemo, then walking back across the hospital to her space in a hospital room full of strangers.

Felicidade’s personality was not warm. She carried herself a bit distant and sad, and she rarely opened up about her own inner struggles. When she did make known what she was feeling, it was nearly always pain. Her trusted Layne with the intimate details of her cancer and her body. As is often the case with cancer, Felicidade was stripped of privacy and dignity by her illness. Felicidade invited Layne behind the curtain of her soul and she trusted Layne to create space between the anguish of late stage cancer and her nerve endings. It was difficult.

When she began a new line of chemo, one which required 5 days of continuous IV treatments, I drove her to the hospital with a heavy heart. It is never an easy week for our patients who need to be admitted and lately they have needed it more than not. Still, I did not think hard on the consequences of walking her to her bedside, carrying her small backpack full of clothes and toiletries and a few snacks, and giving her a smile and a shoulder squeeze as I left her there.

Four days later I got a call at about 5 AM from the nurse on staff. Felicidade had died early that morning in her bed, struggling to breathe.

How worthless are my prayers I know,

yet, Lord forbid that I should go

into the fires of endless woe.

Azarias came smiling to my car and my home in August last year.

His one good eye beamed and he expressed how happy he was to become a part of the Casa Ahava family upon his arrival. His home and family were remote and, though I did not know it at the time, he had been in neither for a matter of years. Azarais’s stoicism in the presence of pain struck me as paradoxically exceptional and, strangely common. While it is impossible to have a true sense of the pain someone else is going through, I have found myself consistently astounded at what I imagine the pain levels of many of my patients to be, given the extent of their illnesses, wounds, and treatments. I have caught myself several times falling into the expectation that chemotherapy and radiation therapy are just “not that bad” given the grace and patience with which many of my patients undergo their horrors. Azaraias was no exception to this and his flint-faced approach to the rigors of chemotherapy contributed to my unconscious downplaying of its effects.

The exceptionality of his patience in the face of pain showed itself when, as I would help him with his daily bandage changes, he would tell me that he did not sleep at all the previous night as a result of the intense pain in his head and eye (the location of his tumor). I found myself simply staggered at his ability to function given how deeply and consistently Azarias’s pain impacted his life. To my own shame I often looked for ways to discount the accuracy of his words, assuming they carried less severity of meaning than the plain understanding of them. I still have much to learn in this work.

The last morning I spoke with Azarias, I woke to find him sitting outside, his body sweaty and his eye bleary. I was preparing to take another patient to the hospital and he was sitting on one of our outdoor couches near the door to her room. Despite his clearly difficult night, he smiled at me and he used an uncommon word (for him) to describe his current state. “Estou aguentar, Jon” he told me. “I am holding on” or “I am enduring” he said. His smile was strained but faithful. His breath was shallow but consistent. And he told me he would see me when I got back from the hospital.

Three hours later Azarias went to his room to try to get some rest and fell asleep on his bed. He did not wake.

When the doomed can no more flee

from the fires of misery

with the chosen call me

Joana spoke poor Portuguese but even in her limited vocabulary she expressed how eager she was to escape the bowels of the hospital in which I found her.

Her large protruding tumor above her right breast was a constant ache, was constantly in the way, and was a constant reminder of the death she carried in her body.

We have had other patients in the past who spoke little or no Portuguese and I am always left with a distinct feeling of an impassable chasm that exists between us simply because we do not have the same words with which we spell out and describe the world. I often heard the fear behind the rudimentary Portuguese words Joana used to ask her questions about how bad it looked when I changed her bandage. I often saw the sadness in her face when she heard that her chemo would be delayed again because her blood levels were just not high enough to start.

But I so rarely heard it in her voice. She was gentle, she was kind, she was shy.

Her open necrotic wound continued to grow and she developed a chronic antibiotic resistant infection. Her chemo was just not helping. We have a small couch reserved for conversations surrounding topics like that and so when I called her to come sit on that couch with Pedro facilitating the language transfer, she knew what she was there to discuss. In her beautiful Xitshwa language, she explained that she had had a dream of her whole family singing the funeral songs over her and lamenting her death. When I asked her if that made her afraid she quickly said it did. At first glance it was easy to assume that she feared that dream heralded her death and that she was afraid of dying. When I pressed just a little bit, “What is it that you are afraid of, Joana?” her bold response was not that she was afraid of dying. It was that she was afraid of dying here. The family funeral songs being sung were for one who had not died at home. Joana belonged to Mabote, her family name and the name of her village. Joana belonged to her people and to her land and she was afraid her death would be among neither.

Last month Joana went home to die and to have the funeral songs sung over her for one safely where she belongs. Last week her wound was bigger, she was weak and afraid, but she was home.

Joana is where she belongs.

Before You, humbled, Lord, I lie,

my heart like ashes, crushed and dry,

assist me when I die.

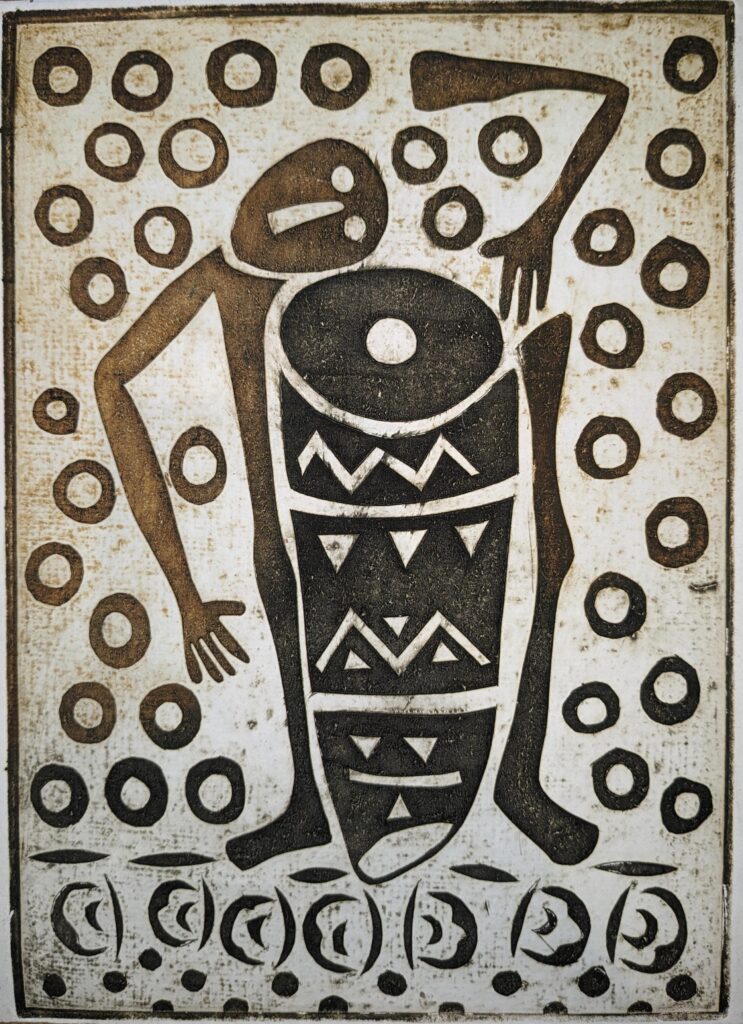

There is a Gregorian chant called the Dies Iræ! Dies Illa. The music of that chant created by an unknown Franciscan monk 800 years ago and its trochaic meter intertwines ascent and descent before finally descending in a falling scale. For several hundred years, long before the formal study of death and death trajectories were created, this music has represented death and dying in theatre and the performing arts. Only later have we come to see the musical representation often approximates the energy and strength of the dying person waxing and waning then falling steadily in a morbid resolution of its fatalistic melody.

Since December the power of that chant has cast its spell over me as I have held the broken pieces of my soul in a tenuous grasp on sanity while death has walked the hallways of Casa Ahava.

Come murmur with me the final lines of this call, this chant, this spell. Come hope for rest for the restless, peace for the weary, and a bit of joy in dark places.

Lord, all-pitying, Jesus blest,

Grant them thine eternal rest. Amen.